THREE ATTITUDES TO DEATH

Written by Vladimir Moss

THREE ATTITUDES TO DEATH

There are three basic attitudes to death: the tragic, the trivial and the triumphant.

The tragic was often superbly expressed by the pagans of antiquity, and even more by the Jews of the Old Testament. Death is tragic because it brings to a definitive, final end everything that we value in life: love, pleasure, beauty, talent, health, glory and honour. The pagans deeply lamented this, and therefore counseled their fellow men to seize the good things of life with as much passion and courage as possible, because it will all pass soon. Carpe diem – seize the moment, because it will pass, it will pass forever and ever. There is perhaps no more heartbreaking story in world literature than that of Orpheus and Eurydice. Orpheus the great musician is granted, for the sake of his great musicianship, to lead his beloved wife out of hades - on condition he does not turn to look at her before they are both back in the light and among the living. However, longing just to take a peep at his beloved, he looks back too early, while she is still in the dark – and loses her forever.

That is, of course, a myth; but there is a similar, but true story in the Bible. God has mercy on the family of Lot, and an angel leads them away from burning Sodom. But they are forbidden to look back at the scene of death and destruction. However, Lot’s wife looks back – and is turned into a pillar of salt.

The Jewish understanding of death is deeper than that of the pagans because they understood the cause of it – the sin of man. It is because Adam and Eve disobeyed God in the Garden of Eden that they and all their descendants were condemned to death. In the Old Testament, there was no consolation to soften the edge of this universal tragedy. Even the righteous went down into hades, a dark, shadowy place with no joy nor exit. Even the righteous Jacob contemplated death with a tragic bitterness: “I shall go down mourning to my son Joseph in hades” (Genesis 37.35). In the Old Testament there is no doctrine of eternal life with God in Paradise. Some of the prophets hinted at a better future, but these hints were not understood until the Coming of Christ. Death was as tragic for the Jews as for the pagans.

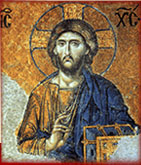

But then came Christ, and our understanding of death was transformed. There was still tragedy – the Lord wept in front of the rotting corpse of his friend Lazarus. But to the widow of Nain, whose only son had died, He said: “Weep not”. And this was not just the conventional, weak comfort that we give to bereaved relatives. For He touched the bier and her son was raised from the dead. There were healings and miracles in the ancient world. But none like this one. And none like this Healer, Who offered, not temporary palliatives or mere prolongation of life on earth, but eternal life in heaven.

For by offering the perfect Sacrifice or Propitiation for sin, Christ removed the root cause of death and thereby granted eternal life to all those that believe in Him. Death now need not be a tragedy – or only a partial, relative, temporary tragedy. Death now can be, and is for all true Christians, an entrance into an eternal life of boundless joy with God and all His saints. How unbearable would death be, says St. John Maximovich, if we had no hope of seeing our reposed relatives in Paradise. But it is bearable precisely because that hope truly exists for true Christians.

So for the true believer death is now, not a tragedy, but a triumph, an entrance into a new and far better life in which there will be “neither pain nor sorrow nor sighing”.

However, contemporary Christians have turned the triumph not merely back into a tragedy but, still worse, into a triviality. First of all, they do not really believe in the power of Christ’s Sacrifice on Golgotha, nor in His resurrection from the dead – without which, as St. Paul says, our own forgiveness and resurrection are unthinkable. Secondly, they reject the infallible word of Scripture: “It is given to men to die once, and then the judgement” (Hebrews 9.27). No, there will be no judgement, they say! God is too merciful to judge or condemn anybody; we will all be saved, we will all go to Paradise!

How senseless, how profoundly unserious and superficial! If God is so merciful that all will be saved, why does He say the exact opposite on so many occasions? And why does He not remove death and suffering right now, and take us all into Paradise – now! What is the point of this purgatory of life on earth, if we are all going to be saved? And why use the word “saved”, when there is in fact nothing to be saved from?

“Okay, perhaps Hitler and Stalin should go to hell,” reply the trivia-mongers. “But not we decent, caring, civilized people. And still less the Buddhists, the Hindus, the Moslems, the Jews, the ordinary atheists who cannot help being brought up in their non-Christian environments and families. The logic of ecumenism rests on the denial of judgement and an overwhelming sense of pride. Ultimately - with one or two exceptions – we are all “worth it”, as the advert says. For we are the judges, not God.”

But perhaps there are some who are still more “worth it”, still more caring, because they don’t believe that even Hitler and Stalin will go to hell. Perhaps the Jehovah’s Witnesses are right, and these monsters will simply cease to exist at death, just like all the evil people that ever lived. After all, the idea of anyone suffering for eternity is just so unbearable, so uncivilized, so unworthy of the idea of a loving God!…

After all, aren’t we all victims anyway? Victims of class prejudice, or national prejudice, or colour prejudice, or gender prejudice? How can such victims be judged for anything? Indeed, perhaps even Hitler and Stalin were victims of their environments, of bad parenting. Indeed, if Darwinism, that doctrine of original death is true, and we are all just the chance products of piece of overheating matter that exploded 14 billion years ago, then it makes no sense to judge anyone for anything. God is dead, and with his death there died any sensible – that is, scientific - concept of good and evil.

Such thoughts, which would have been unthinkable only a few years ago, are commonplace now: the descent of modern man into madness seems inexorable. And yet we haven’t reached rock-bottom yet. The rock-bottom is to deny, not simply the Justice of God after death, but death itself…

As Daniel Hannan writes, “What if we could halt the degeneration of cells, and so halt ageing itself? A quiet revolution is underway in gerontology. Twenty years ago, physical decline was seen as inescapable, and the various conditions associated with old age – heart failure, diabetes, Alzheimer’s and so on – were viewed as discrete diseases. Senescence itself was thought to be beyond the reach of medical science.

“We are now witnessing a vertiginous shift. Rather than treating the separate manifestations of old age, biotech companies are categorizing old age itself as a disease, and searching for a cure. Why, after all, should cells die?”[1]

Will we never learn? Death and taxes are the two inescapable accompaniments of life – and death is the more inescapable of the two. Did not the serpent in the Garden contradict God, saying to Eve: “Thou shalt not surely die”? And did not the previously sinless and immortal Adam and Eve then learn humanity’s first and hardest lesson – that all sinners die.

The tragedy of pre-Christian death, having been transformed into triumph by Christ’s resurrection from the dead, and into trivia by our post-Christian society is now fast descending back into tragedy again. Only the tragedy is deeper and darker than before. For however hard man tries, he cannot completely forget the promise of eternal life given to Him by Christ and realized in the lives of millions of true Christians. Death is a blessed gift to fallen man because it constantly reminds him, in the midst of all his vanity and vainglory, that all this is dust and ashes. It is the one fact of his life which he can never deny and which will always bring him back to the reality of his humiliation. But if he denies even the undeniable, the one supreme and inexorable fact of life, then the prospect before him is truly tragic: he will let that opportunity given him by Christ, Who holds the keys of death and hell in His hands, disappear, never to return; like Orpheus, he will see the vision of true life and love vanishing forever into the dark mists of hell.

September 27 / October 10, 2017.

[1] Hannan, “ My 14-month old might live to see the end of human ageing”, Sunday Telegraph, 8 October, 2107, p. 16.