TWO CROSSES

Written by Vladimir Moss

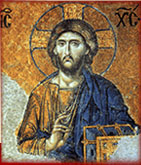

TWO CROSSES

On the Sunday of the Holy Cross, the faithful are exhorted by the Lord to take up their crosses and follow Him (Mark 8.34). At the end of Great Lent, however, the emphasis changes. We are exhorted to take up, not our crosses, but the Cross of Christ: “Today the grace of the Holy Spirit has gathered us together, and we all take up Thy Cross and say…”[1]

What is the difference between the two kinds of Cross – Christ’s and our own?

The cross is first of all the symbol of suffering. Both the Saviour and those who are saved by Him suffer. But the nature of the suffering in the two cases is very different.

Christ did not have to suffer. Not only is He impassible (without suffering) in His Divine nature. In His human nature, too, He did not have to suffer. For suffering is the result of the fall; it is the wages of sin, as St. Paul says; it is the punishment and correction imposed on fallen human nature by God in recompense for the fall. Adam and Eve did not suffer before the fall in any way; they suffered only after it. Thus according to the great God-seer, St. Seraphim of Sarov, Adam’s nature “was created to such an extent immune to the action of every one of the elements created by God, that neither could water drown him, nor fire burn him, nor could the earth swallow him up in its abysses, nor could the air harm him by its action in any way whatsoever. Everything was subject to him…”[2]

The same is true of the human nature of the New Adam, Christ. At the Annunciation, the Holy Spirit descended upon the Holy Virgin Mary and cleansed her of all sin, both personal and original. (Contrary to Roman Catholic teaching, she was conceived in original sin, like all her ancestors, and so was subject to suffering and death.) So the Lord was conceived with a wholly perfect and sinless human nature. He neither sinned personally, nor did He receive original sin from His Mother. Therefore he did not have to suffer or die. But He willed both to suffer and to die in order to sympathize (which literally means: “co-suffer”) with us to the utmost. Every moment of His life on earth He willed to suffer what we suffer – only without sin (Hebrews 4.15).

We see this most clearly in the temptation in the wilderness. “When He had fasted forty days and forty nights,” we read, “afterwards He was hungry” (Matthew 4.2). This is a most supernatural hunger! For for forty days and forty nights He did not suffer any hunger pains: only afterwards did He decide, of His own free will, to suffer hunger – forty days’ worth of hunger pains all at once! So all the sufferings of Christ during His earthly life were the result, not of the physical and psychological laws that govern human nature in its fallen state, but were willed by Him upon His sinless nature -which did not have to suffer at all. Thus every time He hungered he willed to hunger, every time he suffered any kind of pain He willed to suffer it.

Still more appallingly, He willed to take to take upon Himself the sins of the world, thereby destroying them. For us the guilt of sin is tormenting – but only to the extent that we realize its horror, which we rarely do because of the desensitizing effect of our general sinfulness. But for Christ, in the words of Metropolitan Philaret of New York, “every sin burned with the unbearable fire of hell”.[3] Therefore when He took upon Himself the sins of the whole world, - in St. Paul's striking and paradoxical words, "God hath made Him to be sin for us, Who knew no sin" (II Corinthians 5.21) – the torment and the suffering of His sinless human soul were strictly unimaginable. As St. John Maximovich writes: “It was necessary that the sinless Saviour should take upon Himself all human sin, so that He, Who had no sins of His own, should feel the weight of the sin of all humanity and sorrow over it in such a way as was possible only for complete holiness, which clearly feels even the slightest deviation from the commandments and Will of God.”[4]

That Life Incarnate should then die was still more unimaginable. Of course, “God did not create death”, and therefore death is unnatural. But for us death, though unnatural in essence, has nevertheless become in a certain sense natural – in the same sense that sin has become natural or “second nature” to us since the fall. However, there was nothing in the slightest natural about death for the sinless Lord. As Archbishop Averky of Jordanville says, “Death is the consequence of sin (Romans 5.12,15), and so the sinless nature of the God-Man should not have submitted to death: death for it was an unnatural phenomenon: which is why the sinless nature of Christ is indignant at death, and sorrows and pines at its sight.”[5]

Vladimir Lossky writes: "The earthly life of Christ was a continual humiliation. His human will unceasingly renounced what naturally belonged to it, and accepted what was contrary to incorruptible and deified humanity: hunger, thirst, weariness, grief, sufferings, and finally, death on the cross. Thus, one could say that the Person of Christ, before the end of His redemptive work, before the Resurrection, possessed in His Humanity as it were two different poles - the incorruptibility and impassibility proper to a perfect and deified nature, as well as the corruptibility and passibility voluntarily assumed..."[6]

*

Let us now turn from the Cross of Christ to our cross. Of course, it is strictly impossible to compare the suffering of the God-Man, Who was able to accommodate within His sinless soul the suffering and the guilt of the whole of humanity, with the narrow, exceedingly limited suffering of our sin-laden souls – limited, moreover, precisely because of our sinfulness. Nevertheless, we shall dare to make some comparisons.

First, whereas all the sufferings of the Saviour were voluntary, most of our sufferings are involuntary. We are born as fallen beings into a fallen world, and so are subject of necessity to the laws of that fallen world. Thus we do not hunger when we choose to, as the Lord chose; we hunger when our blood sugar and other physical variables fall below a certain level, sending signals to our brain – and all this is beyond our power to modify significantly.

And yet the Lord tells us to take up our cross – that is, act, not simply suffer. And we can act in various ways. The first is by refusing to grumble about our sufferings, thereby turning involuntary suffering into something accommodated in, because accepted by, our will; which may be called making a virtue out of necessity. There is an enormous difference between suffering without knowing or caring why or from whom our sufferings come, and suffering in the full knowledge that they are sent by God to correct and purify our souls. Therefore, says St. Paul, “let us not complain, as some of them [the Israelites in the desert] also complained, and were destroyed by the destroyer” (I Corinthians 10.10).

The refusal to grumble or complain is but one example of self-denial, which the Lord commands even before He tells us to take up our cross (Mark 8.34). We deny ourselves whenever we say no to an impulse of our fallen nature: whether that would be to complain about our sufferings, or to indulge in sexual activity outside marriage, or to take revenge on someone who has injured us. This is the beginning of the cross, a form of asceticism that all Christians must practice. A higher stage is attained when the Christian practices the following voluntary acts: not only not complaining about suffering, but rejoicing in it; not only refusing to indulge in unlawful sexual activity, but embracing the virginal life; not only refusing to take revenge on his enemies, but doing good to them. This is not just self-denial, but taking up the cross.

The feats of the holy martyrs and monastic saints represent the highest peaks of cross-bearing. (St. Theodore the Studite said that the sorrows of monasticism reap the same reward as the pains of martyrdom.) Insofar as they constitute the highest, most complete transformation of involuntary into voluntary suffering, they come closest to the imitation of Christ crucified.

However, a radical difference must still be recognized.

For however great the voluntary sufferings of the saints and martyrs, they are not in themselves life-giving or salvific. For we are saved, not by works, but by faith. Or rather, there is one work that saves – the work of believing in Christ. For “’what shall we do,’ asked the people, ‘that we may work the works of God?’ Jesus answered and said to them, ‘This is the work of God, that you should believe in Him Whom he hath sent’” (John 6.28-29).

In order to understand why this should be so, we need to look more closely at the parallel which the Holy Fathers draw between our cross and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, on the one hand, and the Cross of Christ and the tree of Life, on the other. Two trees engendering two forms of life, and two forms of suffering. But only one of them is salvific, as having Life in itself.

The tree of the knowledge of good and evil represents our fallen human nature separated from God. For it was in the centre of the garden (Genesis 3.3), where God, not man, should be. For from the point of view of the still immature nature of Adam and Eve, it was their own nature, with its needs and desires, that was at the centre, rather than the glorification of God. These needs and desires were not yet corrupted; but they were still not concentrated exclusively on, and united to, Life Itself and therefore fixed in goodness.

St. Gregory the Theologian says that the tree of Life was the contemplation of God. But Adam and Eve’s immaturity meant that they were not yet ready for contemplation. Therefore God commanded them not to partake of this tree until they had reached spiritual maturity and immovability in the good.

But what can be wrong with a knowledge of good and evil? Nothing in itself. Nor is the tree evil in itself, in its essence; for it was made by God, Who made all things “very good”, and it was truly “pleasant to the eyes, and a tree desirable to make one wise” (Genesis 3.6). Human nature is not evil in itself, and it is designed to acquire a knowledge of good and evil, that is, of wisdom. But only in and through the tree of Life, the divinely human nature of Christ.

In separation from the true of Life, the knowledge of good and evil in the proper sense becomes a knowledge of something subtly different – the knowledge of pleasure and pain, that is, of what is considered good and evil by fallen men, but is not in fact truly good and evil. For our whole life, as St. Maximus the Confessor said, swings between the poles of the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. The knowledge of how to obtain the “good” and avoid the “evil” is born of experience in the fall, and is inevitably imperfect; it cannot ascend beyond the good and evil of the fallen world to what is truly “beyond good and evil”, that is, to the realm where there is only Good. Far better, therefore, to acquire wisdom from the tree of Life, so as to be established immovably in the true Good before encountering sin and suffering, like the Divine Child in Isaiah Who “shall eat curds and honey, that He may know to refuse the evil and choose the good” (7.15).

The tree of Life, by contrast, represents, not fallen human nature and the wisdom that is attainable by fallen beings, but the unfallen divinely human nature of Christ, Who is Wisdom Incarnate. In the context of the New Testament Church it represents the Body and Blood of Christ, partaking of Whom we are delivered from the corruption engendered by our eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and are given true Life. Adam and Eve were barred from the tree of Life after their fall because, having allowed their nature to be corrupted by sin and not having repented properly, they would have made their corruption eternal; their participation in the Holy Mystery would have been to their condemnation.

Fallen man is crucified on the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and is completely unable through his own works to free himself from this torment. However, with the eyes of faith he sees another tree – and another Man crucified upon it. Like the wise thief on the cross next to Christ’s, his faith connects him with the Man; the two crosses are united, and the grace and power of the One quenches the evil energy of the other.

But in order to see the Cross of Christ, and experience its regenerative power, we have to ascend our own cross, repent of our sins and crucify our own fallen desires to the best of our ability. Only then will we, like the wise thief, be able to enter Paradise carrying our own cross behind Christ’s. For it is only “through the Cross” – Christ’s Cross – that “joy has entered the world”.[7]

March 7/20, 2017.

Monday of the Week of the Holy Cross.

[1] Triodion, Great Vespers of Palm Sunday, “Lord, I have cried”, troparion.

[2]St. Seraphim of Sarov, Conversation with Motovilov, in Fr. Seraphim Rose, Genesis, Creation and Early Man, Platina, Ca.: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2000, p. 442.

[3] St. Philaret, Great Friday sermon, 1973.

[4] St. John, “What did Christ Pray about in the Garden of Gethsemane?”, Living Orthodoxy, N 87, vol. XV, no. 3, May-June, 1993.

[5] Archbishop Averky, Guide to the Study of the Holy Scriptures of the New Testament, Jordanville: Holy Trinity Monastery, volume 1, 1974, pp. 290-291.

[6] Lossky, The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, London: James Clarke, 1957, p. 148.

[7] Pentecostarion, Mattins of Pascha, ikos.