Orthodox Christian Books – the collected works of Dr Vladimir Moss

-

A Century of English Sanctity by Dr Vladimir Moss

-

THE LAST TIME RUSSIA FELL UNDER THE CURSE

by Vladimir Moss Today is the feast of the first-hierarchs of the see of Moscow, and therefore the historical leaders of the Russian Church, both metropolitans and patriarchs. For what should we be especially praying to them? The greatest need of the Russian land at the present time is not the ending of the war,…

-

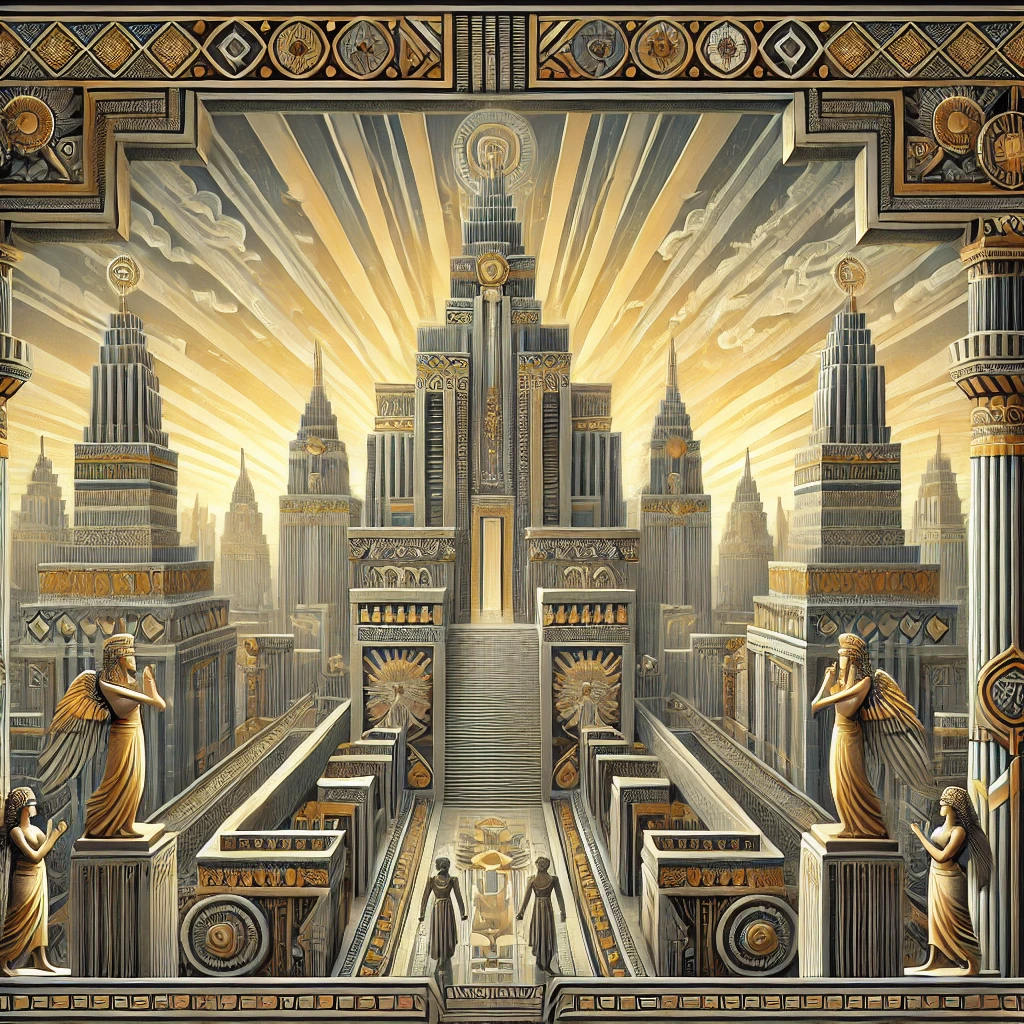

Nimrod’s Babylon

NIMROD’S BABYLON Post-diluvial civilization began, as one might expect, not far from where the ark landed in the mountains of Ararat – that is, in Mesopotamia, at the headwaters of the Tigris and Euphrates. Perhaps the earliest state discovered by archaeologists was that centred on Arslantepe in south-east Turkey, where a king’s throne and signs…

Got any book recommendations?